The emotional impact of baby loss is long lasting. You might feel shock, numbness, anger, resentment, sadness, emptiness, guilt, self-blame, loss of self-esteem, and many other emotions. While this can be difficult to accept, it is important to grieve for your loss and to do what you need to receive support. Some people may change the subject if your baby is mentioned, or unknowingly say insensitive or hurtful things. They may not know what to say or are frightened of causing more distress. Many bereaved parents say that some friends and acquaintances cross the road to avoid having to talk to them, or may stop talking to them completely. You might find it helpful to view this animation and to recommend it to family and friends so that they can support you: https://www.sands.org.uk/get-involved/sands-campaigns/finding-words

It is possible that you might grieve both for the loss of the baby and for the loss of your own hopes and dreams. Until the 1980s, the death of a baby was often dismissed as unimportant and most parents did not receive much understanding or support. Parents were likely to have been told to forget about their baby, to have another, and to carry on as though nothing had happened. However, even with sensitive and supportive care, the grief that follows a baby’s death may remain for a long time.

It is normal to experience strong emotions of sadness and loss but you may find that your grief lasts for longer than you expect. If you are still finding it hard to manage everyday life or to work after several months, you may want to seek professional help. You can make an appointment with your GP and explain how you are feeling. They can refer you for specialist help and support if needed and you may also like to seek counselling directly. Please do get in touch with us and we can support you with this.

You may already know someone who has experienced the death of a baby or you may have had this experience previously. Comparing your grief to that of another parent, or to yourself during a different baby loss, may not be helpful as each bereavement is different and everyone grieves differently. You might, however, find it beneficial to talk about your experience.

There are various theories of grief. We are including two of them here as these might help you understand and explore your grief over time. At no time is there the expectation that you should be “fine” or feel “normal”.

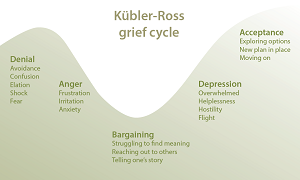

One theory, by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, talks about the five stages of grief, namely denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. These stages do not necessarily happen one after the other; you might find yourself at any stage at any time, or perhaps experience a combination of any of these stages.

Lois Tonkin’s model talks about “growing around your grief”. The idea is that your grief remains intact and that your life grows around it.

The grief of losing your baby initially takes up almost every part of you, but as time goes on and with support, your grief does not diminish but other aspects of life grow around it enabling you to find a new kind of normal.

There are many ways to express grief. These vary from person to person and can also change over time. Being aware of what you need will help you grieve in a way that is right for you.

Many parents contact Sands for support. You can contact our helpline, share your experiences with others on the online community, attend a local Sands support group, contact a local Sands befriender. Sands support is available for as long as you need.